Labour Day: a history

Originally posted on Medium in 2017

Even as we sometimes grumble about our 40 hour work week feeling so long as we sit in comfy chairs with climate controlled offices, it’s a relatively new invention and a bloody one to have achieved. Be thankful you’re not a 9 year old kid working 60 hours a week in a dirty, dangerous industrial factory.

There’s no formal anniversary for ideas, but it is sort of special to note that the first songs sung about 8 hour days started in 1817, a mere 200 years ago.

The first implementation of an 8 hour work day was in Soviet Russia in 1917 as part of the October Revolution, and it took a few more decades of uphill battle for it to catch on around the world from there.

So, why did something so seemingly obvious take 200 years of fighting?

1817

By now the industrial revolution had been spreading across Britain for roughly 40 years. Factories were built, smokestacks filled the sky with cotton white steam power and soon after black oily coal burn.

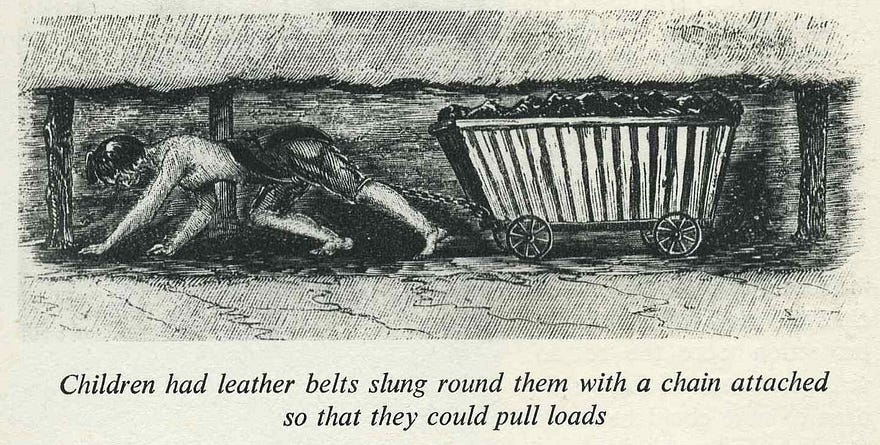

There were no labour laws. Men worked 16 hours a day, 6 days a week and women / children ‘got it easy’ with a mere 10 hour day, with really no minimum age for working other than size and usefulness. Arguably, the small size was also an advantage for working inside chimneys as sweeps and in the small tunnels of coal and iron mines. Plenty of work either way.I’m not kidding, this was a real thing. That could be your child.

Somehow, it took a radical to look at this and say “yeah, that seems… cruel”

So James Deb and Robert Owen started to campaign against it, and almost everyone hated them for their socialist poppycock ideas.

This would be the trend for the next 200+ years.

Interestingly, Robert Owen had started in 1810 with a 10 hour work day because 16 hours was literally killing folks, but moved to an 8 hour ideal in 1917. I couldn’t immediately find an answer for ‘why eight?’ but it was half of 16 and also lead to a nice chant:

Eight hours work, eight hours rest, eight hours free

Which is pretty tidy at both a mathematical and branding level. There’s 24 hours in a day, and we know humans sleep roughly 8, so the other 16 can be divided equally as well. Great!

And, since these were liberal socialist poppycock spouters, they also wanted crazy things like equal work hours for men and women, and that the children maybe shouldn’t be squeezed into dust for baron capitalist profits.

1833

The Factory Act of 1833 comes to rescue the British children and says kids aged 9–13 could only work 8 hours a day, six days a week. What a relief! Kids aged 14–18 could work 12 hours. Under age 9 was school. I found some interesting textbooks that’ll come up later on.

Across the pond, labour in early America is getting uneasy, and Irish coal heavers stage the first labour strike with the slogan:

From 6 to 6, ten hours work and two hours for meals.

…which admittedly is not as catchy as the 8:8:8 one.

Boston ship builders start their own 8 hour day in 1836 because no one could really stop them; they didn’t have a union nor needed to strike and no one could replace their specific workmanship skills. So they just… did it.

1840–50

New Zealand and the Australian Workers Union have success with the first widespread eight hour day, but no one else seems to have heard, know or care. They’re islands on the other side of the world, and a quiet footnote.

1847–48

Workers in England won themselves a ten hour work day, mostly.

Napoleon, painted by Alexandre Cabanel

Napoleon, painted by Alexandre Cabanel

Workers in France won twelve, after two bloody revolutions and the overthrow of King Louis Philippe. What sparked it wasn’t necessarily ideological, but survival: Philippe’s government was closing what essentially was unemployment services so the underworked were starving and those who still had jobs were overworked and underpaid, so everyone was angry.

They lost 10 000 men, and 4000 more were banished from France.

The uprising wasn’t necessarily successful, but it did lay the groundwork for immediate subsequent actions that instated Napoleon Bonaparte, who was generally pretty good at his job until he died.

1866–67

The various communist, socialist and anarchist powers were consolidating over time and had formed The International Workingmen’s Association, which by 1866 had enough workers on board to demand an eight hour day. They had more men than the police did, and as such started to throw their numbers and weight around more aggressively. But, their goals weren’t aligned quite enough, and the communist / anarchist ideological schism split the association a decade later.

In 1967 Karl Marx is watching all of this and writing Das Kapital about how the baron capitalists were literally working people to death and it was widely unsustainable for society — you can’t be productive if you’re dead. So, instead, we should have lower hours and longer lifespan productivity + a more enjoyable life with more hours of rest and leisure, which everyone was (heh) dying for anyway.

1886

Chicago. The American civil war was fading from memory a few decades ago and new threats were arising locally: unions, strikers, barons, policemen and various splinter groups of communist, anarchist and socialists were all vying for power of hearts and minds.

Chicago was covering the Franco-Prussian war too, which was a war against “communists and atheists” - both ideas a scary affront to the puritanical capitalist Christian American and should be stopped at all costs. This is where Napoleon made some bad military decisions and lost France, so it seemed like the communists were winning and spreading.

This arguably was the first Red Scare in America.

There were skirmishes: some unions would strike, the capitalist barons would be upset that their factories aren’t running and hire some police to ‘accidentally’ rough up the folks sitting in front of the fences. Anarchists were hung for their treason to American life and became martyrs.

Everyone was scared. Ideologies were a new weapon bigger than guns.

Then, in 1871, the Chicago fire happened because the entire town’s buildings, sidewalks and roads were made of wood. Rumours say it was a communist plot, others say it was a cow that kicked over a lantern in a nearby barn, perhaps it was insurance fraud — but it killed 1000 people and left 100 000 other homeless, rebuilding 17 000 buildings. Looting broke out in the streets and martial law was enacted, bringing in nearby companies of soldiers to help quell the lawless aftermath.

So, they were a bit distracted from the whole labour thing for a while.

Just as a side note, as much as this isn’t really a religious war it sort of is a religious fight: we have to understand the context of why people were even against less work in the first place, and why it was seen as a bad thing or a threat to a puritanical America (and Britain, France, “the west”).

The christian (namely protestant, calvinist, catholic) doctrine is steeped in work ethic because James 2:14–26 says that ‘faith without works is dead’ and this got construed literally into an idea that working hard is the only way to salvation of yourself, and contributing to your neighbour. This subverted the previous Jesus: “…it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God.” Matthew 19:24 quote.

Early American presidents had to be self-made men, log cabin types and rugged individuals who worked for their position. They saw what happened with leisurely silver spoon kings in the various european monarchies and rejected that for politicians who could fight wars and bears with gumption.

“Idle hands are the devil’s play-thing”

Side note within a side note: I was researching textbooks from the 1800s to see what kids even learned in school before they were sent to the mines and here’s the first random page I opened to:

You can read the whole book (and many others) here, and they’re all drippingwith this sort of language. The Second / Third Great Awakening evangelical events are really fascinating and worth talking about sometime.

There was a very real worry that people given 8 hours of free time a day would become a) disenfranchised from the church but b) genuinely dangerous as humans. That sort of free time is how witches come to be. That sort of free time is how people plan bank heists and build bombs in their barn and come to expect the ills of socialized welfare while the ‘good’ workers are dragged down and punished by the lazy people. That we need work in order to feel purpose and be fulfilled because said work = godliness.

Sound familiar? I won’t talk about automation, but uhhh, automation.

1917

The first World War has been in swing for a few years now, but countries are still sorta sorting out their internal problems and Lenin + Trotsky stage an uprising while everyone is distracted by international battlefronts.

The October revolution in pre-but-becoming-soviet Russia succeed a bunch of liberal reforms: the 8 hour day, equality of men and women, allowed for cohabitation of sexes, divorce and abortion, decriminalized homosexuality and generally gave all people more autonomy than they previously had.

Unfortunately, this autonomy mixed with the busy war efforts (and a civil war barely after WWI) meant that women weren’t having as many babies as they used to and this was seen as a problem for the long term survival of economic and military power, so as things were taken back by Stalin in 1936 he basically wholesale reversed all the progress they had made.

Still, this is the first widespread 8 hour work day (other than Australia, who, again, everyone forgot entirely about) and conveniently 100 years ago.

At risk of getting distracted, it should be noted that this uprising was considered treasonous and evil. They were radical terrorists who wanted to instate the evils of equal gender rights and murdered Nicholas II to get it while the loyal army was off fighting the war. As much as we talk about the American ideals, basically every country denounced the liberal poppycock of lower work hours and human rights issues. It was simply bad for business.

1919

Okay, almost there.

Following World War 1 the League of Nations was created and the International Labour Organization with it, a third party group representing government, employers AND workers all together in a ratio of 2:1:1.

World War 2 happens, but once things are back on track it’s a pretty smooth delivery from there: the post war prosperity in America (and indeed, the world) leaned back towards leisure as an ultimate goal, something I’ve talked a lot about elsewhere, and the modern technologies and time saving inventions of the jet and atom ages bring a lot of automation that the dirty coal factory human labour type industrial revolution era was leaving behind.

This ILO brings with it four charters:

The right of workers to associate freely and bargain collectively;

The end of forced and compulsory labour;

The end of child labour; and

The end of unfair discrimination among workers.

…and this was official in 1998, so really recent. They’d been working hard on this the whole time, and obviously more ‘civilized’ countries had ended child labour and things earlier in good taste, but forced and child labour does still exist today, so there’s work yet to be done.

Enjoy labour day a little bit harder! Every second you spend lazing on the couch reading Medium posts for free on your electronic whizbang doodad you aren’t working in a coal mine. Curl up a little tighter, feel the warmth of that blanket a little more, enjoy how not filthy your skin is, how unblackened your lungs are. Breathe in, breathe out. Wow, so clean.

And hey, you might be dreading going back to work tuesday, but at least it’s only 8 hours of unforced labour, and you might even get to sit down. Crazy communists took up guns and gave their lives to fight for that right.

Happy long weekend!

Last updated