#16 School of Rock

Alternate titles: Rockstars. Queens of the Stone Age. That’s Gneiss.

Originally posted as part of the PHD in Curiosity newsletter, 2016

This is a rai (like raay) stone:

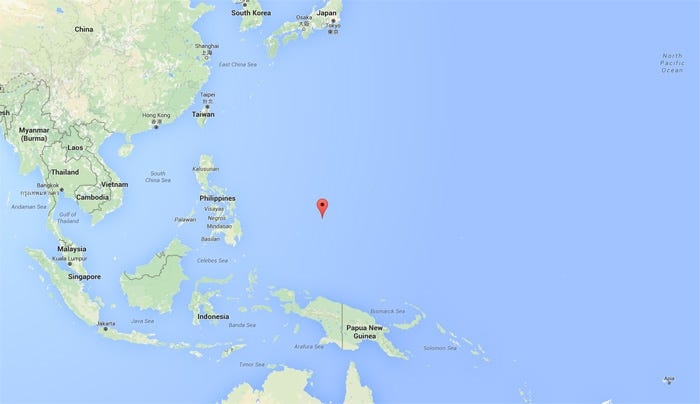

And as you can see, it’s a big rock with a hole in it. We’ll get to that in a second. For context, they’re found on an island called Wa’ab, or more modernly Yap. If you’ve never heard of it you’re forgiven since it’s so small that it’s actually a sub section of a sub section of Micronesia — yes ‘micro’ as in tiny. The entire island is smaller than Calgary, but while Calgary is dense city this is a south Pacific island and is as expected largely jungle. Modern populations around 11 thousand (they do have an airport), much less in the primitive days where our history takes place.

Think of these rocks as big coins. The problem was, it was a lot of work to carry big 4 ton limestone disks jangling around in your loincloth pocket, so they set them down next to their houses or along the roads and never moved them. Ownership was established and agreed entirely by community: you might buy something and give another villager your rai like we would give money, but the rock always sat under the same mangrove patch there. Your worth was just known, people all agreed that those rocks were yours and you could use them as currency since populations were such that everyone could keep track of who had what. It was completely transparent net worth.

And, naturally, the bigger and more ornate your rock was, the more it was valuable.

But size and craftsmanship weren’t the only value attached. These rocks came with stories.

The internet research on this is dubious at best (although there’s a 1991 essay by Milton Friedman about these stones and the American gold standard) but there is a story where a rai stone sunk on its way between islands (did I mention they quarried these limestone beasts on a different island 250 km of pacific ocean away? That they, in the 2nd century, had bamboo canoe-type boats strong enough to work with this ridiculous weight? They say that’s why the holes exist, so the rocks can be speared between catamaran style hulls) and was still honoured as a currency. Physically it’s no different than the ownership agreements of the land-sitting rocks, it’s just a little to the left and a lot deeper down. Sure you can’t see your money-rock, but can any of us modern folk point to our money on the banking app of our phone? So, the one at the bottom of the ocean was still just as real as any.

Is it any wonder that they were considered inherently valuable? They were exotic and the methods for getting one were laborious at the very least and often deadly, there was literally a number value to each rock based on how many people died bringing it to rest on the island. Similar tales of struggle and toil attached to specific stones made them extra valuable — they were hard to bring in and thus worth more. Supply and demand. Makes sense.

But! in 1871 an Irish American ship captain David O’Keefe shipwrecked on the island and brought with him iron tools and more modern know-how. He used his tool technology to carve rocks faster and easier than ever which made him incredibly rich (he was king of his own even tinier island in the end) but ultimately caused an inflation so powerful that it devalued each existing rock to the point of collapse. And, the Germans bought the whole area in the south Pacific in 1898 after the Spanish-American war. The rocks are still used today, but it’s a lot more symbolic and traditional. The younger folk don’t seem to appreciate them the same as they used to.

Anyway. I tried telling all of this to the cashier at the popcorn counter of the movie theater and she still wouldn’t take my ripped $5. The rip was story and a much better one than Age of Ultron could ever be.

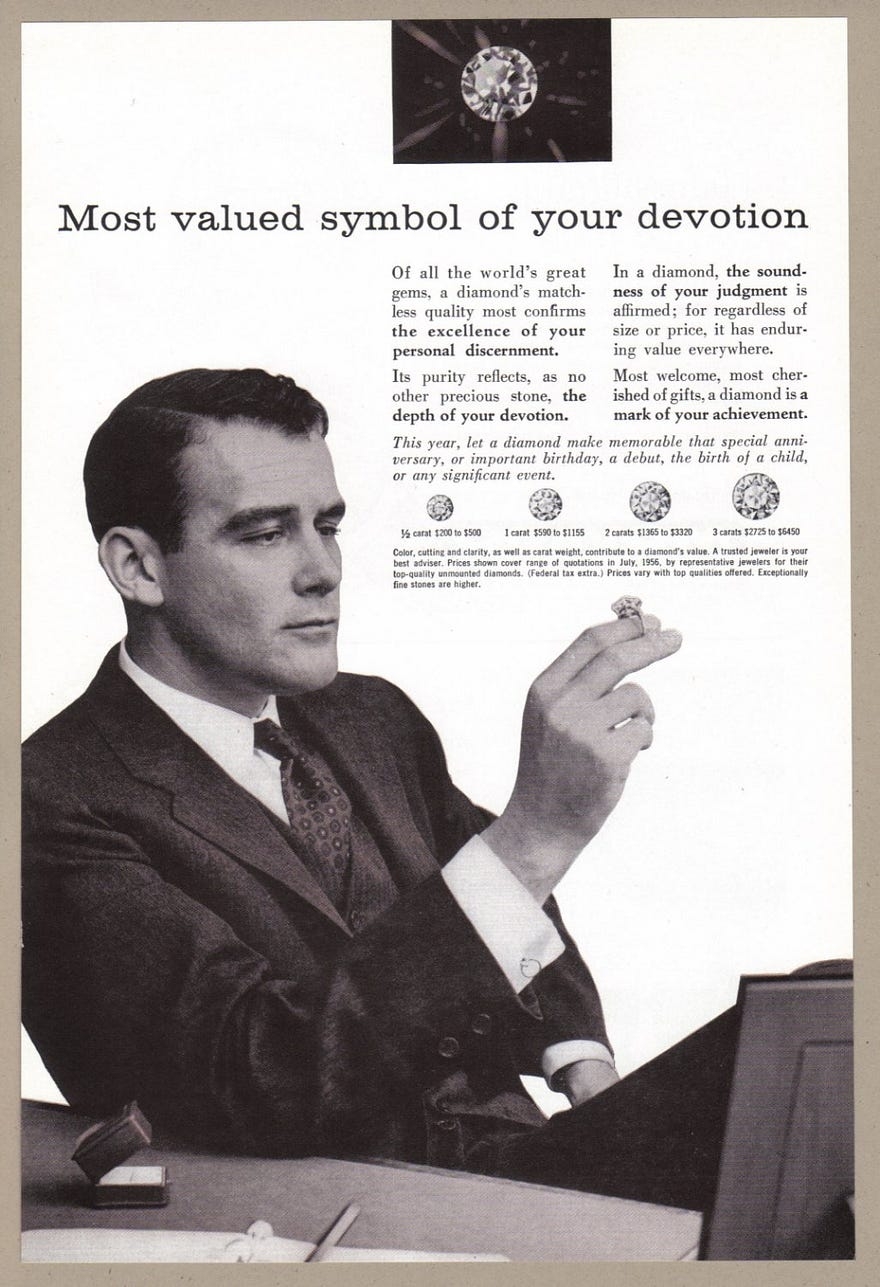

This is barely even conspiracy it’s so well known and acknowledged: diamonds are artificially inflated in value. There’s warehouses of ’em in Siberia and supply is kept very well choked to raise demand year after year. They’re largely sold on the same pretenses that they were in 1938 when De Beers turned them from a small and dying market into a massive status symbol of a man’s love for his gal, of his wealth and success in life. He turned a market that rich people didn’t want and poor people couldn’t afford into one of celebrity marketing and the Royal family themselves were photographed to great success. Diamond sales exploded in three years even during The Great Depression. The value increase was so carefully calculated and steady ever since that people started buying them like an investment in the 70’s. Turns out that’s a terrible plan since the resale value is minimal; although the entire market value rises every year as a singular object they depreciate faster than driving a new car off the dealer lot. After all, “diamonds are forever” — but that too is just clever marketing.

Check out those bold words: The excellence of your personal discernment. The depth of your devotion. The sound-ness of your judgement. A mark of your achievement.But there’s a better story here. A story about rocks and the speed of light.

Did you know light goes through diamond at 40% of its normal speed?

(Normal speed being a vacuum, air itself is slower than that but index of refraction numbers are always calculated from vacuum. I tried to shine a flashlight into my Dyson and didn’t learn anything at all except that it’s very dusty inside)

It’s true though. Light speed is related to density, even though it’s considered a constant it’s actually always changing depending on what it’s cruising through. Refraction (that bent straw illusion in a glass of water) is because water is denser than air. If you had a glass of diamond inside your glass of water you’d see it bend again.

It gets cooler (literally) in cave diving with sections called thermocline and halocline — bodies of water sitting on top each other that are different temperatures and salinity respectively. Here’s a thermocline:

See how there’s a sort of “surface” there where it hits the walls of the cave? How this tree debris in the foreground sort of looks like it’s on land? Notice how the bubbles going up prove that this entire place is under water?

That’s density.

The trick is, we’re so used to seeing the surface of lakes and water bodies that our brains tell us that those signs are a surface between water and air, but in fact here it’s water and warmer water. Less dense water. Water where the light is moving faster.

But it gets trippier.

Density is time travel.

Without getting into Lorentz and Einstein and time dilation of relative motion and all that quickly-complicated garbage, we can agree that the light coming from really distant things is old, right? The Earth wobbles a few million kilometers towards and away from the sun on its elliptical orbit so it’s always a little different, but the time it takes for the sun’s light to hit us in the eyes is roughly 500 seconds; 8 and a bit minutes. That light is 500 seconds old. Should the sun suddenly blink out, it would take us 500 seconds + our reaction time to realize that it’s gone. It would be off and the light would still be travelling and travelling, like a long train that’s running into us until the end finally catches up and at the end is darkness, the light train has run out of cars.

All light works like this, by the way. There’s some very (very) tiny amount of time after you turn your kitchen light off where there’s just photons plowing through the room and bouncing off things after the bulb is actually off. The bounces take energy (and the air itself is scattering) so eventually those rays die after the source is dark, but they’re there briefly. Something like 3 nanoseconds per meter traveled.

Okay. All of that was a long way to say: if space was made of diamond, it would take the sunlight much longer to get here — the index of refraction for diamond is 2.4 (water is ~1.3, glass is 1.5) which means those 500 seconds just became 1200 seconds, or 20 minutes.

If the sun blinked out, we wouldn’t know it for an additional 12 minutes in diamond space. We’d have bigger issues, of course. The gravity of a solid solar system sized diamond, the inability to orbit or rotate as a planet, the lack of basically any life being able to form or grow. We’re talking about a planet without pizza, alright? It would be a totally calamity.

But! time travel. We’d be 12 minutes later to the celestial party. When you hold up and look through a diamond, you’re seeing the past. You are with any material, mind you, but especially diamond because high density. 2.4x longer. What you see through that shape is just a little bit older than what you see around it.

Side note, and I realize this whole tangent got way out of hand already, but there’s also a speed of gravity which is effectively the same as the speed of light — it’s the speed of field propagation. That means as the Earth is flinging around the sun it’s actually flinging around where the sun was 8 minutes ago. The sun’s orbit around the center of the Milky Way is also lagging by it’s distance and so on. If the sun disappeared completely, it would both take time for the light to stop and the gravitational pull on the planet itself to be severed, our centrifugal inertia shooting us out into space.

There was a science fiction book with a really brief scene that always stuck with me. I wish I could remember the specific book but I think it was an Asimov — the scene was that there were house windows that were so dense they’d take years for the light to come through. It was a ghost town that he was walking through, but he could see all these families laughing and smiling in the windows because they were “playing back” what happened on the other side of them years earlier. If you walked into the dark empty house you could also look out and see a busy street and living trees and so forth outside, from years ago.

I always liked that idea. Density is time travel.

This started off as a look at the relationship between rocks and value over history. I was going to talk about bronze and silver, of the iron Lobi snakes found in Ghana and of the Californian Double Eagle coin — a gold rush era $20 chunk of actual gold that was indeed worth its weight in gold and probably one of the most gorgeous coins ever designed. Of Canadian Tire money, perhaps, and how it’s somehow accepted at a shocking number of stores as real currency despite just being paper money that a store printed for long enough that it’s engrained in our Canadian psyche.

Oh well!

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Last updated